When I was in high school I bought a used electric guitar at my local music store. It was this beautiful homemade instrument shaped a little like a Les Paul with a striped neck made from two different types of wood that ran from the head through to the end of the body. The case was lined with deep red velvet and when you opened it the overwhelming scent of wood varnish seemed to add to it's authenticity. A professional musician passing through town had sold it - I imagined it might have a rich, mysterious history.

An interest in music was definitely the common denominator for my group of friends but I never really had the confidence or initiative to organize like they did. I played my guitar with my dinky amplifier turned down very low during jazz band at school. A few of my friends made a Ben Folds Five-esque trio and did a great job playing a school function. I remember sheepishly hauling my guitar over to my friend Tyler's house for a jam session - he played the bass. Although I knew how to play, turning it into something individual, unguided, and self-expressive was much harder than playing the notes of a sheet of music. I dinked around and gave up after a half hour. Music was definitely a gateway to my teenage community, though, a knowledge base that had been introduced to me by others, expanded on my own in my bedroom with headphones, and then turned into a means of relating with my peers. For the girls of We Are The Best it serves the same function, allowing a pair of punk-loving 13-year-olds in a post-punk world to define themselves and distinguish an identity that helps them grown up and learn about the same stuff the rest of us have to deal with at some point too: friendship, family, love & politics, In other words, life.

Set in Stockholm in 1982, We Are The Best opens with 13-year-old Bobo at her mother's birthday, sitting sulkingly while everyone goes about the celebration. Then the worst happens and she is noticed by her mother on the way to her room and she becomes the center of attention. She complains on the phone to her best-friend Klara the same martyr's cry of preteens the world over: "My mom is the worst. She's so embarrassing." Klara disagrees. "My parents are the worst. Just listen to them" and then she holds to the phone out the door to hear an argument about laundry. Both girls are punk rock in a disco pop age. Klara gets grief about her mohawk and impassioned pleas about the perils of nuclear power from the other girls at school. Both are called ugly and despised by others. One night on a whim at their local youth center they decide to make their own punk band. Mostly they just bang on the drums and bass available in the common rehearsal space. They enlist their overtly Christian classmate Hedvig to help them because she actually knows how to play music, albeit only classical guitar. She's also an outcast and they bond over their first song about how much gym class sucks called "Hate the Sport."

The whole thing is joyously fun and as the trailer says, it for anyone who is 13 years old, will be 13 years old, or was 13 years old. The director, Lukas Moodysson, hits every beat just right balancing the touching moments as you watch these girls form and strengthen their friendships, deal with boys getting in the way, and fight a riotous audience at their coming out concert. There are plenty of laugh out loud moments. I really loved Hedvig's character and how she provided an opportunity for Bobo and Klara to realize the merit of compassion. Hedvig is more mature than the other two but also benefits in the relationship by learning to have fun and let her hair down (or actually, to cut it off). Even though Bobo and Klara are anti-God and anti-religion they get a taste of how Christianity has punk rock roots as they see the courage Hedvig has to be herself even when it's not popular.

One token of a great movie is that it helps you expand your circle of humanity. I've never found MMA cage fighting to be enjoyable, and yet while watching Warrior I was on the edge of my seat. You might never have associated punk music with the fragile yet hilarious stage of life of coming-of-age of preteens but through these girls' characters you come to love punk music for the opportunity it provides them to grow up and accept new people. Although they might resist the notion, the love these girls develop for each other is just the same that a group of cheerleaders might. We Are The Best reiterates the fact that you already knew that life for punk rockers is pretty much the same as it is for the rest of us. Roger Ebert said, "The movies are like a machine that generates empathy." This is something I'm always looking for and We Are The Best takes you into the space of being a 13 year old. From a goofy dad that wants to embarrass you by bringing a clarinet to your punk band rehearsal to the joy of serendipitous friendships turning into lifelong relationships, this movie reminds you of yourself - whether you've had the same experiences or not - in a fresh way.

We Are The Best is currently streaming on Netflix.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Friday, November 7, 2014

Interstellar

For some reason the vast, incomprehensible expanse we know as space inspires some of the greatest filmmakers to want to tell great stories about family relationships. It's not that big of a mystery: contemplating the infinite and immeasurable is daunting, almost traumatic, when confronted full in the face. When facing the possibility of complete oblivion and meaninglessness it seems natural to focus on what is most meaningful and dear and search for significance there. Most recently there was Alfonso Cuaron's Gravity taking a John Donne-sian ("No man is an island") approach comparing the isolation of space to social remoteness. Another great entry of this type is Robert Zemeckis's Contact, doing a more traditional, but no less inspiring, take on the "are we alone?" question based on the theories of Carl Sagan. Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey holds legendary status, and rightly so, as he partnered with Arthur C. Clarke, one of the greatest sci-fi writers of all time, to examine the existence of humanity itself. Heck, even Steven Spielberg took a couple cracks at it with E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. And now Christopher Nolan books his entry in this impressive field of work with Interstellar, a visually-stunning and powerful movie arguing for nothing less than the literal cosmic power of love.

Ok, if you can handle the very last little bit of that last paragraph (singing only a little bit of Huey Lewis & the News to yourself) then you are prepped and ready for Interstellar. There are one or two moments during Christopher Nolan's expansive IMAX-ready epic that tackle that point very directly and I commend him and his brother and writing-partner, Jonathan, for putting some bare moments in the film that really cut back the layers to communicate so directly to the audience. Because despite its seemingly formidable length (2 hours and 49 minutes that flew by), Nolan seems to have ensured that every bit of the movie serves the story and provides cinematic and entertainment value.

One of the most obvious of a number of elements that make Interstellar a masterpiece is a great cast. Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, and Jessica Chastain are top-level actors on par with the high-level talent that Nolan is able to attract to his projects (Hathaway having worked with him previously on The Dark Night Rises). McConaughey plays Cooper, an astronaut-turned-farmer in a world that's dying and a society that's given up on space travel - and almost science altogether. Mackenzie Foy plays his young daughter Murph and shares the part with Chastain as her adult counterpart: the two actresses fit the character nicely. Coop and Murph stumble (or do they?) on an old mentor/teacher of Cooper's, Professor Brand played by Nolan-regular Michael Caine, who has a use for his unused astronaut skills. Anne Hathaway is Brand's daughter Amelia, a member of the crew planning to travel through a wormhole that has popped up near Saturn and seems to provide some promising prospects for a second home for humanity. Epic interstellar-ness ensues. As the film progresses Nolan tackles the theory of relativity and black holes. The support cast, including a surprising unbilled cameo, inspire excitement and confidence.

At the heart of the story is the relationship between Coop and Murph. In an article in The Guardian, Nolan reveals that part of what drives this movie is his reflection on his own relationship with his children. Let that idea sink in as you're watching. Interstellar dives into some pretty heady relativistic theory that, in essence, means his daughter is aging faster than him. Their relationship goes through some traumatic episodes and, when considered by the film's end, covers decades of time with very little direct interaction from the point that he leaves on his mission to "save the world." The core of what Interstellar examines, rather than the reality of relativistic space travel and the decline of the human race (both of which are explored believably and thought-provokingly, each deserving of their own analysis) is how the bond of love between these people somehow makes a real, physical, and lasting connection.

Visually, Interstellar is the direct descendant of Kubrick's aforementioned 2001. Nolan takes the audience past the rings of Saturn, through a wormhole and into a number of unique environments that are truly worthy of comparison with 2001. If you've ever had the chance to see Hubble 3D at an IMAX theater then you have a taste of what you're in for here. Filmed on it to a greater proportion than any of his previous films, Nolan's preferred format for viewing this movie is on 70mm IMAX film. Luckily I live mere minutes from a properly-outfitted theater. Did you know a true IMAX screen is a giant square? Nolan takes full advantage of the format's capabilities, providing, through both sight and sound, the most "immersive" experience possible. I must say that the Sacramento Esquire Theater didn't disappoint and I highly recommend taking advantage of the opportunity to enjoy this movie as its creator intended (find a theater here). The fuller picture and core-breaching sound provide a sensational, cinematic experience that makes a pickup driving through cornfields, a shuttle-like blast off, and relativistic space travel equally enthralling. It's worth it just for that aspect alone. Apart from stunning imagery and great acting, Hans Zimmer's score and some truly amazing and dynamic sound design round out the most obvious pieces of what makes this movie great.

Ok, if you can handle the very last little bit of that last paragraph (singing only a little bit of Huey Lewis & the News to yourself) then you are prepped and ready for Interstellar. There are one or two moments during Christopher Nolan's expansive IMAX-ready epic that tackle that point very directly and I commend him and his brother and writing-partner, Jonathan, for putting some bare moments in the film that really cut back the layers to communicate so directly to the audience. Because despite its seemingly formidable length (2 hours and 49 minutes that flew by), Nolan seems to have ensured that every bit of the movie serves the story and provides cinematic and entertainment value.

One of the most obvious of a number of elements that make Interstellar a masterpiece is a great cast. Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, and Jessica Chastain are top-level actors on par with the high-level talent that Nolan is able to attract to his projects (Hathaway having worked with him previously on The Dark Night Rises). McConaughey plays Cooper, an astronaut-turned-farmer in a world that's dying and a society that's given up on space travel - and almost science altogether. Mackenzie Foy plays his young daughter Murph and shares the part with Chastain as her adult counterpart: the two actresses fit the character nicely. Coop and Murph stumble (or do they?) on an old mentor/teacher of Cooper's, Professor Brand played by Nolan-regular Michael Caine, who has a use for his unused astronaut skills. Anne Hathaway is Brand's daughter Amelia, a member of the crew planning to travel through a wormhole that has popped up near Saturn and seems to provide some promising prospects for a second home for humanity. Epic interstellar-ness ensues. As the film progresses Nolan tackles the theory of relativity and black holes. The support cast, including a surprising unbilled cameo, inspire excitement and confidence.

At the heart of the story is the relationship between Coop and Murph. In an article in The Guardian, Nolan reveals that part of what drives this movie is his reflection on his own relationship with his children. Let that idea sink in as you're watching. Interstellar dives into some pretty heady relativistic theory that, in essence, means his daughter is aging faster than him. Their relationship goes through some traumatic episodes and, when considered by the film's end, covers decades of time with very little direct interaction from the point that he leaves on his mission to "save the world." The core of what Interstellar examines, rather than the reality of relativistic space travel and the decline of the human race (both of which are explored believably and thought-provokingly, each deserving of their own analysis) is how the bond of love between these people somehow makes a real, physical, and lasting connection.

Visually, Interstellar is the direct descendant of Kubrick's aforementioned 2001. Nolan takes the audience past the rings of Saturn, through a wormhole and into a number of unique environments that are truly worthy of comparison with 2001. If you've ever had the chance to see Hubble 3D at an IMAX theater then you have a taste of what you're in for here. Filmed on it to a greater proportion than any of his previous films, Nolan's preferred format for viewing this movie is on 70mm IMAX film. Luckily I live mere minutes from a properly-outfitted theater. Did you know a true IMAX screen is a giant square? Nolan takes full advantage of the format's capabilities, providing, through both sight and sound, the most "immersive" experience possible. I must say that the Sacramento Esquire Theater didn't disappoint and I highly recommend taking advantage of the opportunity to enjoy this movie as its creator intended (find a theater here). The fuller picture and core-breaching sound provide a sensational, cinematic experience that makes a pickup driving through cornfields, a shuttle-like blast off, and relativistic space travel equally enthralling. It's worth it just for that aspect alone. Apart from stunning imagery and great acting, Hans Zimmer's score and some truly amazing and dynamic sound design round out the most obvious pieces of what makes this movie great.

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Blancanieves: A reminder of great silent film

|

| Daniel Gimenez Cacho plays the father and bullfighter extraordinaire, Antonio Villalta |

|

| Maribel Verdu is the wicked Stepmother and she plays it so well |

But we must remember Ebert's Law: "A movie is not about what it is about. It is about how it is about it." This movie is really all about the joyful, more visceral experience of watching a silent film. Striving to adhere strictly to the genre of the silent films of the 1920's and 1930's, it serves both as a reminder of the magic of that format and as a marker of the advancement of film technology. You may never have seen a silent film (if so, shame on you. Go watch The General), but even if you've watched the latest the Transformers movie you've seen, heard, and felt the effects of things learned and innovated through silent film. The next time you watch a movie, think about the different purely-visual mechanisms that are used to display emotion, to further the plot, or to introduce a new character. There is an efficiency in the tactics used that is not only effective in communicating something to the audience, but in doing it in an entertaining way.

As for the modern take on the genre, Blancanieves strives to capture the essence of the original reference material while using updated technology to add clarity and a few flourishing touches. It was filmed in color which was afterward taken out, giving it a brighter tone with a beautifully-crisp, high-def feel. It goes beyond The Artist by cutting down the aspect ratio to a more traditional size. Although this followed The Artist by a year or two, Berger thought of the concept of the film back in 2003 and had been working on it since that time. That The Artist beat him to the punch may have stolen some of his thunder in the race of PR and marketing, but that in no way detracts from the quality and accomplishment of this movie. It is certainly overlooked and worth more than one watch.

|

| The misfit band of dwarves |

Tuesday, July 8, 2014

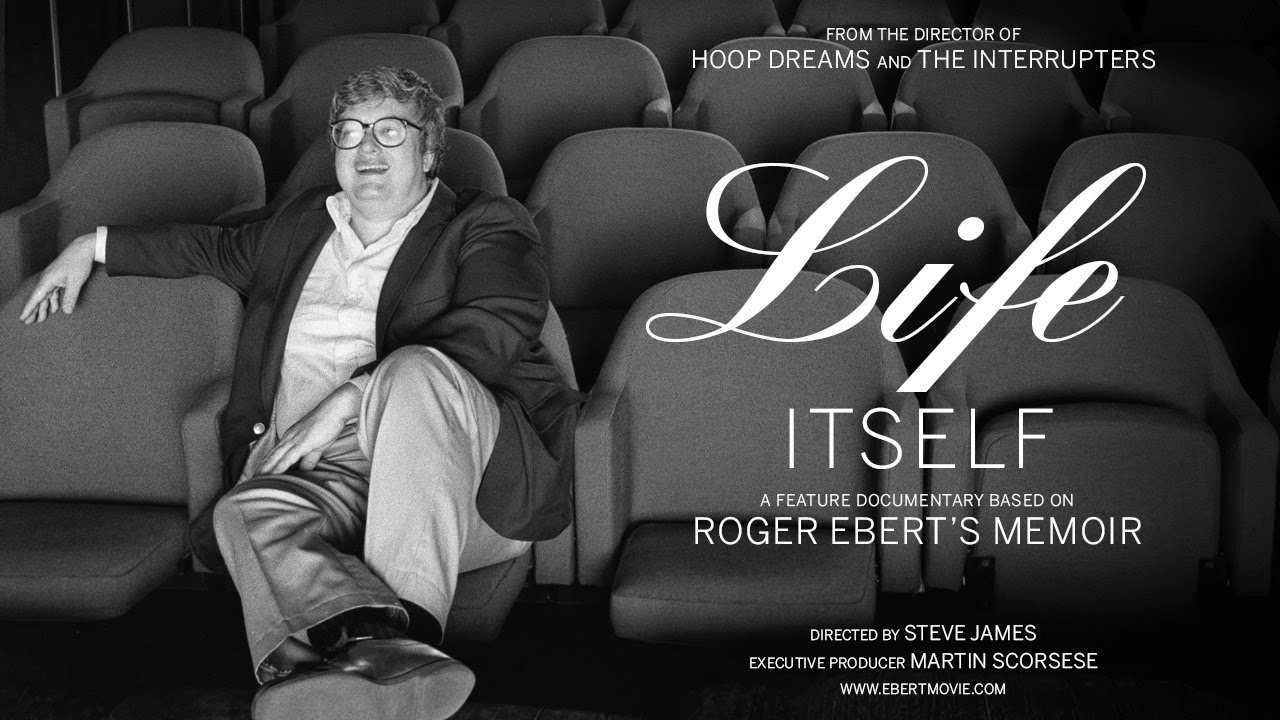

Film: Life Itself

Perhaps you've had the opportunity to have a friend who shares your taste in movies, books, and music enough that you know you can always turn to that person for a fun and meaningful discussion about whatever it is you've recently been watching, reading, or listening to. You look forward to talking to this friend because when you agree it is so validating to have someone understand how you see things, and because when you disagree there's no one you want to convince more. Starting around 2007, Roger Ebert slowly became this friend for me, until it became almost impossible to watch, or consider watching, a movie without seeking his perspective. And just to clarify - yes, I did have friends in real life too.

Like many of my generation, all I knew about Ebert for years was that there was a TV show with a couple of guys talking about movies, Siskel & Ebert, and a catchphrase, "Two Thumbs Up." I had seen the show occasionally on PBS, and I remember watching it after Siskel passed away and it became Ebert & Roeper, with Richard Roeper. So when I was in college and found myself getting more interested in getting a critic's take on movies I had watched and kept seeing Roger Ebert's reviews pop up in searches online, it was natural for me read his reviews. The vague sense of the history behind the name seemed authoritative and most times I wasn't interested in reading more than one critic's review. Then, over time, I started to realize I often agreed with Roger. And not only did I agree with him (most of the time) but I found that he would frequently put words to my feelings, explaining how I felt but with more eloquence. After a while it became routine for me to read Roger's reviews of movies I had seen or was thinking about seeing.

Part of the reason I was drawn to Roger's site, rogerebert.com, was because he had been successfully making a concerted effort to grow his online presence. As an early adopter to online and mobile technology, like Twitter, Ebert had been touching a new generation of movie nerds and I was part of that wave. After dealing with cancer for years his jaw was removed, making it impossible to speak. In 2008, right as I was realizing how much I enjoyed Roger's writing, he had written his first blog post and was entering what would be the final stage of his life and career, in which his celebrity and popularity grew more than ever before.

Roger Ebert passed away last year and now I don't have that friend to turn to - at least not for any new movies. More importantly, though, his family, friends, and followers feel the absence of his positive and life-affirming perspective. The documentary film about Roger Ebert, Life Itself, was just released last weekend. It is a beautiful biopic that expertly takes the audience through Ebert's life, extracting, along the way, the essence of what made him tick so that it teaches a few things about *ahem* life itself.

I was in San Francisco over the weekend and so I had an opportunity to do something I'd never done: See a film while it was in limited release. My wife, Karen, and I saw it on one of 23 screens showing it around the country. We were seated in fancy electric-reclining leather chairs. We were uncomfortably in the front row of a tiny theater, giving me a headache by the end of the show (which cost us $25). These things didn't really bother me all that much, though, because the movie itself was an honest, sometimes humorous, touching, warts-and-all portrayal of a man I admired.

The story is told through a mix of interviews with family, friends, and colleagues, along with archival footage of Roger from his show with Gene Siskel, a mix of photos and written artifacts, and then new footage shot by the director, Steve James, during the final months of Roger's life. Using those final days and weeks as a foothold, we jump back in time moving through the different eras of his life: growing up in Illinois, college days as editor of the newspaper, the start of his professional life and his alcoholism, his growing fame, the TV show and relationship with Siskel, his marriage with Chaz, his family, his illness, the growth of his popularity online, and then his death and the response of fans and loved ones.

In his review, Matt Zoller Seitz, editor-in-chief of rogerebert.com, writes that it is about two loves stories: that of Roger with his wife and now widow, Chaz, and the relationship with with rival/partner/brother-in-spirit Gene Siskel. The segment covering his contentious, big-brother/little-brother type partnership with Siskel and the 30+ years they did their TV program together is perhaps the longest and most interesting section of the film. You get some great footage, both that aired on the show and some behind the scenes outtakes, that show their wit, competition, and sometimes disdain for one another. It'll send you looking for old footage from the show on YouTube, of which there is quite a bit. In an interview that Chaz did in promotion of this film, she said that during the years that Roger was doing the show she learned to steer clear of the studio on the days they would record. Roger would get riled up, sometimes excited he had "bested" Siskel, sometimes infuriated at Siskel's seeming blockheadedness. You can understand why when you see the footage in Life Itself.

One interesting tidbit that you might not know if you're not an Ebert fan is the connection between Roger and the film's director, Steve James. As a young, aspiring filmmaker, James made a 3-hour long documentary in the early 90's called Hoop Dreams, about a couple of black, inner-city youth hoping to find a path to a better life through their basketball talent (on Netflix Instant now). Told in a very straightforward and compelling way, the movie really impressed both Ebert and Siskel. Their positive reviews and championing of the film led to the purchase of its distribution rights and jump-started James' career as a documentary filmmaker. And so it's an added value to the beauty of the movie knowing a bit of its director's background. You don't get that story in the film as James humbly focuses on other indie directors whose work and careers benefited from Ebert's desire to find great movies from unknowns.

When I stepped into the world of Ebert I was unaware of almost all of this history. I was just touched by his writing, which some in the film share became even better in this final phase of his life. Ebert was sometimes criticized for being too lenient of a critic, doling out positive rating mores often than his counterparts across the country. But that's because of at least two things. First, he considered it his role to help people find movies that they will like, and that meant reviewing it based on who the audience of a movie was and what their expectations would be - not comparing it always against the greatest films (see the heated discussion on Benji the Hunted from the movie). The second was that Roger loved movies and wanted to love a movie when he saw it. He was always looking for the next great film and the story that it told. This, primarily, is what made him such a well-loved critic. And that attitude towards movies seems to be an extension of his attitude toward life, especially in his later years. That comes out in his writing and it comes out beautifully in this movie on his life.

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

Edge of Tomorrow

Edge of Tomorrow is the first original action blockbuster of the summer and likely to be, of them all, the biggest success. The others would be Snowpiercer and Lucy, both of which seem pretty unique and come from directors with solid reputations (the former comes out in August and the latter started in limited release last week). The premise and plot of this film feels familiar, like its been pieced together from varying parts of iconic blockbusters from the past 25 years, but it tells its story so well that you don't mind. The most oft made comparison is as a sci-fi action iteration of the masterpiece Groundhog Day. And rightly so. There's something in that idea of reliving the same day - of realizing the potential for change that exists inside of 24 hours - that is rich with story-telling potential and that sparks our imagination. Cashing in on that curiosity, Edge of Tomorrow delivers plenty of entertainment as a smart, fun, and emotionally-engaging summer blockbuster should.

In the near future Earth has been hit by a meteoroid containing an alien force that proceeds to attack the human race, taking over much of Europe. A global army is amassed and a special tool, a mechanical suit, turns the average enlistee into a super-soldier, better equipped to fight what are called Mimics - quick, multi-armed, mechanical-seeming aliens akin to the sentinels from The Matrix. Emily Blunt plays Rita, the femme fatale public face of victory for the war against the Mimics. She's a legend, known for having killed over 100 mimics in one battle - she's called the Angel of Verdun to the reverent and the Full Metal Bitch to the fearfully adoring. As the most decorated warrior of the force, and as an icon among soldiers, she holds a special authority, like the Achilles of her time.

Tom Cruise plays Cage, an officer that specializes in PR, spinning stories through multimedia campaigns to help fight the war of public opinion for the army and its leadership. He's a bit slimy at first, but because he's Tom Cruise you can't help but love him. After miscalculating the moral compass of a general, he winds up powerless, reduced to the office of private, labeled a deserter, and with orders to join a D-Day-type invasion happening on the coast of France the next day. He's not the type to fight but you realize that he's going to end up in battle and there's nothing he can do about it. Within a few minutes of joining the battle he dies. And then he wakes up right where he was the day before - about to get processed and assigned to his unit. This shouldn't be any surprise - it's the basic premise of the movie. You can get the details when you watch it, which I recommend you do - but basically he needs to relive this day again and again, ensuring it ends with either his death (causing a reset) or the destruction of the entire enemy force. Fairly early on he confronts Rita and establishes that she's been through this before (although she lost this ability) and that she thinks he can help win the war.

I'll mention Groundhog Day again because much of the second act plays out similarly. You'll have a lot of fun seeing Cage attempt new tactics to advance farther in his mission. After establishing a routine to get the attention of Rita, they set to training and planning the best way to destroy the mimics. Unlike the Bill Murray comedy, though, instead of ending each day after a full 24 hours, Cage's day must end with his death (much like Source Code). This reset-by-death brings a freedom to him that only comes from the knowledge that you can try it all again tomorrow. And this is where the real magic of the situation starts to change Cage and his approach to life and those around him, especially Rita. The confidence he has in confronting those things he's already done over and over again translates into an ability to more expertly deal with the situations that result from his success at getting closer to the goal. We can see that Rita has already reached this level of existence and is glad to have someone who understands.

The real reason we love a movie like this is because we like to imagine taking on every day as if we were an expert at that day. Surely some days feel monotonously like every other day and perhaps we'd like to imagine being put in a situation where we are forced to confront life with a different attitude. Whether or not every day of your life is just the repetition of a routine, the reality is that each day truly is an opportunity to make a world of difference, and just like Phil the weatherman in Puxatawney, PA, realizes the only one trapping you in life is yourself, Cage comes to take control. In the third act the certainty of his regeneration comes into question and the lasting nature of the decisions he makes sets in, but he has a new perspective with which to make them.

The action is straightforward with no shakey-cam because the story demands you know what's happening. The editing style is quick, avoiding the need to repeat sections of the day beyond what is necessary, while rarely devolving into an extensive montage, which the film could easily do. The audience isn't always told which iteration of the day Cage is experiencing and so you're never sure if this is the first or the fifteenth time he's been in this situation until you see it play out. Both Cruise and Blunt play their characters supremely well with convincing chemistry and earnestness.

--- Spoiler Alert!!! --- If you don't want to discuss the ending don't read! ---

While the repetition of the middle section provides the fun and escalating action, the third act brings with it opportunities for some emotional reflection. Without the insurance of knowing he can always try it again, Cage, as you should know if you already watched the film, loses his power to reset. Now on his last chance to live that day, he starts the rest of his life. He comes to grips with the fact that he can't relive the day again. The thing he does keep, though, is the knowledge of the power of change he has simply by using the knowledge and skills he's gained. As he uses that, fighting along side of Rita to the very end, he now is running towards the source of the war instead of away from it as he did at the beginning of the movie. As he makes the ultimate sacrifice at the film's climax, and only after he has given his life, knowing full well he can't have it back, it is given to him again. As he goes to find Rita in the final moments of the film, and as he stares at her and laughs right before the credits roll, he's finally able to envision a future that includes her and now he has the freedom of perspective that enables him to envision a radical reality and to choose to make that happen.

In the near future Earth has been hit by a meteoroid containing an alien force that proceeds to attack the human race, taking over much of Europe. A global army is amassed and a special tool, a mechanical suit, turns the average enlistee into a super-soldier, better equipped to fight what are called Mimics - quick, multi-armed, mechanical-seeming aliens akin to the sentinels from The Matrix. Emily Blunt plays Rita, the femme fatale public face of victory for the war against the Mimics. She's a legend, known for having killed over 100 mimics in one battle - she's called the Angel of Verdun to the reverent and the Full Metal Bitch to the fearfully adoring. As the most decorated warrior of the force, and as an icon among soldiers, she holds a special authority, like the Achilles of her time.

I'll mention Groundhog Day again because much of the second act plays out similarly. You'll have a lot of fun seeing Cage attempt new tactics to advance farther in his mission. After establishing a routine to get the attention of Rita, they set to training and planning the best way to destroy the mimics. Unlike the Bill Murray comedy, though, instead of ending each day after a full 24 hours, Cage's day must end with his death (much like Source Code). This reset-by-death brings a freedom to him that only comes from the knowledge that you can try it all again tomorrow. And this is where the real magic of the situation starts to change Cage and his approach to life and those around him, especially Rita. The confidence he has in confronting those things he's already done over and over again translates into an ability to more expertly deal with the situations that result from his success at getting closer to the goal. We can see that Rita has already reached this level of existence and is glad to have someone who understands.

The real reason we love a movie like this is because we like to imagine taking on every day as if we were an expert at that day. Surely some days feel monotonously like every other day and perhaps we'd like to imagine being put in a situation where we are forced to confront life with a different attitude. Whether or not every day of your life is just the repetition of a routine, the reality is that each day truly is an opportunity to make a world of difference, and just like Phil the weatherman in Puxatawney, PA, realizes the only one trapping you in life is yourself, Cage comes to take control. In the third act the certainty of his regeneration comes into question and the lasting nature of the decisions he makes sets in, but he has a new perspective with which to make them.

The action is straightforward with no shakey-cam because the story demands you know what's happening. The editing style is quick, avoiding the need to repeat sections of the day beyond what is necessary, while rarely devolving into an extensive montage, which the film could easily do. The audience isn't always told which iteration of the day Cage is experiencing and so you're never sure if this is the first or the fifteenth time he's been in this situation until you see it play out. Both Cruise and Blunt play their characters supremely well with convincing chemistry and earnestness.

--- Spoiler Alert!!! --- If you don't want to discuss the ending don't read! ---

While the repetition of the middle section provides the fun and escalating action, the third act brings with it opportunities for some emotional reflection. Without the insurance of knowing he can always try it again, Cage, as you should know if you already watched the film, loses his power to reset. Now on his last chance to live that day, he starts the rest of his life. He comes to grips with the fact that he can't relive the day again. The thing he does keep, though, is the knowledge of the power of change he has simply by using the knowledge and skills he's gained. As he uses that, fighting along side of Rita to the very end, he now is running towards the source of the war instead of away from it as he did at the beginning of the movie. As he makes the ultimate sacrifice at the film's climax, and only after he has given his life, knowing full well he can't have it back, it is given to him again. As he goes to find Rita in the final moments of the film, and as he stares at her and laughs right before the credits roll, he's finally able to envision a future that includes her and now he has the freedom of perspective that enables him to envision a radical reality and to choose to make that happen.

Friday, June 27, 2014

All Is Lost by J.C. Chandor

The title of this film by J.C. Chandor, All Is Lost, is a state of mind that its main character, a solitary old man sailing in the Indian Ocean and played by Robert Redford, does not let himself enter until the utmost moment of loss. Building a story to fit precisely around that idea within the setting given, the filmmaker displays a level of craftsmanship - on his second feature - that leaves me feeling excited for what his career has in store. As carefully orchestrated as Alfonso Cuaron's Gravity and as riveting as the director's own first feature film, Margin Call, All Is Lost is an exercise in basic, concise, and utterly-focused filmmaking. It's a thrill to watch and a pleasure to contemplate.

In an interview discussing the movie, Redford said he was interested in the part because it seemed like it would be a purely cinematic experience. He explained that for him, that meant a very visual narrative, that it could almost be a silent film. As I consider that term, "cinematic," in the context of this movie I think of the strengths that film has over other media for artistic expression. First and foremost is the ability to grab and hold the attention of the audience by providing both sight and sound. And as an extension of that, it is a way to communicate through a sort of mind meld, without the need for an explicit description of what is happening. You just watch, think, and feel. Certainly there are oodles of wonderful films with plenty of witty or dramatic dialogue, narration, or other forms of written and verbal communication. And "cinematic" could also be interpreted many other legitimate ways, but as far as high impact, emotional, and visual storytelling goes, that old, handsome devil is right: All Is Lost is a purely cinematic experience.

Watching the trailer or merely looking at the movie poster tells you all you really need to know of the premise: a man sailing in deep, ocean waters is confronted with a situation that looks like its only headed from bad to worse. It's not too much of a spoiler to say that the burden of helpful resources at the disposal of Our Man (the character's name in the credits) gets lightened throughout the length of the film. Indeed, Chandor explains briefly in a commentary track that the loss (a key word, being part of the title) of each physical item or asset in the film may correspond with an equally distressing, but perhaps ultimately relieving emotional shedding.

The only verbal clue we're given of Our Man's origins is the contents of a letter, read at the introduction of the film but written much later. An excerpt goes, "I'm sorry... I know that means little at this point, but I am. I tried, I think you would all agree that I tried. To be true, to be strong, to be kind, to love, to be right. But I wasn't... All is lost here... except for soul and body... that is, what's left of them..." That certainly seems consistent with common notions of deathbed contemplations. It sounds like a man that realizes he could've done better (don't we all). An allegorical hint we're given comes near the beginning of the struggle as his high-tech navigation gear gets doused with sea water. We see him leafing through a copy of "Introduction to Celestial Navigation," presumably for the first time. Later on he pulls out an unused sextant. You would think if you were doing a major solo trip across an ocean that learning how to get your bearings the old fashioned way would be a priority. You might also think a man in his 70's would have developed a strong sense of spirituality (aka, celestial navigation) throughout life's ups and downs.

For me, the idea of embarking on a journey like this seems noble and brave, and so it's easy to like this guy. His grace under fire is impressive - but also not unrealistic. The serenity and focus with which he confronts a series of disastrous, life-threatening situations just points out that sometimes survival only comes by keeping your head in the here and now. He rarely takes the time to reflect on his predicament. On one hand, that trait is key to his survival. On the other, if we consider that he may have lived his whole life this way, that unreflective nature may be the reason behind what he writes. Perhaps there is a lesson that life has been trying to teach him that won't come any other way.

All Is Lost is another entry in a strain of films, like Gravity, Castaway, or The Truman Show, where learning comes only along with going to the edge of life and deciding to hold on. J.C. Chandor's ability to draw out that essence of the story is a result of a laser-focus on communicating that concept and only making decisions, both planned and spontaneous, that get right at the heart of his purpose. After watching some of the featurettes on the blu-ray you realize that although it's an indie film with a presumably small budget, the filmmaking team is efficient and exacting in the production process, and yet still able to allow the serendipitous, in-the-moment surprises become a part of the movie. I admire that adherence to craft while working in a medium that, by necessity, is collaborative and, I expect at times, desperate. Chandor's a director whose future work I look forward to with anticipation.

Other notes:

In an interview discussing the movie, Redford said he was interested in the part because it seemed like it would be a purely cinematic experience. He explained that for him, that meant a very visual narrative, that it could almost be a silent film. As I consider that term, "cinematic," in the context of this movie I think of the strengths that film has over other media for artistic expression. First and foremost is the ability to grab and hold the attention of the audience by providing both sight and sound. And as an extension of that, it is a way to communicate through a sort of mind meld, without the need for an explicit description of what is happening. You just watch, think, and feel. Certainly there are oodles of wonderful films with plenty of witty or dramatic dialogue, narration, or other forms of written and verbal communication. And "cinematic" could also be interpreted many other legitimate ways, but as far as high impact, emotional, and visual storytelling goes, that old, handsome devil is right: All Is Lost is a purely cinematic experience.

Watching the trailer or merely looking at the movie poster tells you all you really need to know of the premise: a man sailing in deep, ocean waters is confronted with a situation that looks like its only headed from bad to worse. It's not too much of a spoiler to say that the burden of helpful resources at the disposal of Our Man (the character's name in the credits) gets lightened throughout the length of the film. Indeed, Chandor explains briefly in a commentary track that the loss (a key word, being part of the title) of each physical item or asset in the film may correspond with an equally distressing, but perhaps ultimately relieving emotional shedding.

The only verbal clue we're given of Our Man's origins is the contents of a letter, read at the introduction of the film but written much later. An excerpt goes, "I'm sorry... I know that means little at this point, but I am. I tried, I think you would all agree that I tried. To be true, to be strong, to be kind, to love, to be right. But I wasn't... All is lost here... except for soul and body... that is, what's left of them..." That certainly seems consistent with common notions of deathbed contemplations. It sounds like a man that realizes he could've done better (don't we all). An allegorical hint we're given comes near the beginning of the struggle as his high-tech navigation gear gets doused with sea water. We see him leafing through a copy of "Introduction to Celestial Navigation," presumably for the first time. Later on he pulls out an unused sextant. You would think if you were doing a major solo trip across an ocean that learning how to get your bearings the old fashioned way would be a priority. You might also think a man in his 70's would have developed a strong sense of spirituality (aka, celestial navigation) throughout life's ups and downs.

For me, the idea of embarking on a journey like this seems noble and brave, and so it's easy to like this guy. His grace under fire is impressive - but also not unrealistic. The serenity and focus with which he confronts a series of disastrous, life-threatening situations just points out that sometimes survival only comes by keeping your head in the here and now. He rarely takes the time to reflect on his predicament. On one hand, that trait is key to his survival. On the other, if we consider that he may have lived his whole life this way, that unreflective nature may be the reason behind what he writes. Perhaps there is a lesson that life has been trying to teach him that won't come any other way.

All Is Lost is another entry in a strain of films, like Gravity, Castaway, or The Truman Show, where learning comes only along with going to the edge of life and deciding to hold on. J.C. Chandor's ability to draw out that essence of the story is a result of a laser-focus on communicating that concept and only making decisions, both planned and spontaneous, that get right at the heart of his purpose. After watching some of the featurettes on the blu-ray you realize that although it's an indie film with a presumably small budget, the filmmaking team is efficient and exacting in the production process, and yet still able to allow the serendipitous, in-the-moment surprises become a part of the movie. I admire that adherence to craft while working in a medium that, by necessity, is collaborative and, I expect at times, desperate. Chandor's a director whose future work I look forward to with anticipation.

Other notes:

- It's a visually stunning film, despite being so simple. There are over 300 visual effects shots, only a couple of which are obvious, and in these it is only because logically you wouldn't expect them to actually put Robert Redford on a small sailboat in the middle of a raging storm. And there are quite a lot of shots you might be tempted to think are fake but are indeed completely real. He really did jump into that lifeboat.

- Alex Ebert, lead singer of Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros, does a fantastic job with the score. I'll toot my own horn and say that I suspected something in the main theme that very subtly smacked of Edward Sharpe and so I was smugly satisfied when I saw Ebert's name in the credits (I have a witness to confirm this - both my prediction and the smugness).

- Although some have understandably felt that Chandor's two features, Margin Call and All is Lost, are miles apart from each for being so different (I'm look at you Matt Zoller Seitz, I would say he has a penchant for showing people dealing with situations that are falling to pieces before them. That's a line I'm making from only two points, but still, the name of the next movies he's working on is A Most Violent Year.

- Robert Redford gives the performance of a lifetime and it really is too bad he wasn't nominated for an Oscar. Looking back at the field of competition for that award, I definitely think there was some room for him despite the range of talent that were represented.

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

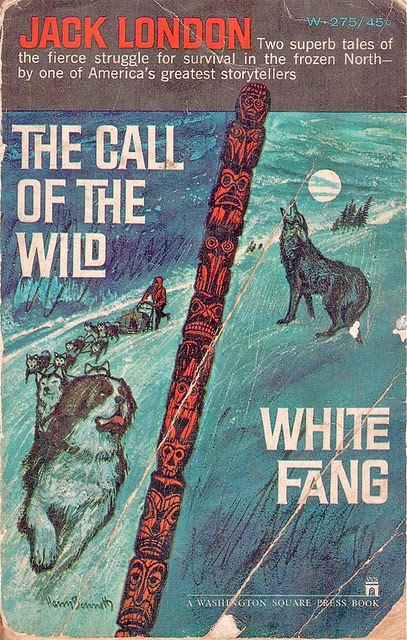

The Call of the Wild & White Fang: The companion novels of Jack London

|

| Photo credit: m.gross196 on Flickr |

-White Fang

Thomas Nagel, an American philosopher I know very little about, wrote an essay called "What its like to be a bat" in 1974. The main point is that one can never truly know what it is like to be someone or something else. Should some power be able to transport the essence of yourself into the body of a bat, perhaps even with some of the instincts of a bat, so that you could then return and report back on the experience, you'll never have actually had the experience of being a bat. Because, by definition, being a bat is not knowing and understanding what it is to be anything else. You would only have accomplished knowing what it is like to be you in the body of a bat. And so truly experiencing what life is like in another's skin is impossible. Even so, Jack London does a helluva job describing the life of a dog in White Fang and The Call of the Wild

I'm really beginning to love Jack London. After first reading The Call of the Wild and now White Fang I am really drawn into his writing. Like Hemingway, London has a relatively bleak style, but the similarity is due more to the shared subject matter than the lack of narrative more characteristic of the former. Both writers spend a lot of time describing very basic, physical processes that suggest a natural state of being. In both of these books by London, the primary point of view is that of a wolf/dog or dog/wolf, respectively White Fang and Buck, and so while human events, actions, and words are described, the only understanding that is spelled out is that which the dog possesses. We must infer anything else that is happening - some is obvious and some unimportant and unmentioned.

They are essentially the same story told in reverse. Which is forward and which is reverse depends either on which you read first or which you prefer. One follows a dog with a bit of wolf in him and his journey from the cushy Santa Clara valley to the hard life as a sled dog in the Alaska wilderness to, finally, complete freedom as a wholly wild animal. The other follows a wolf with a bit of dog in him in the Alaska wild that learns to trust man, fear man, work for man, and eventually winds up in a cushy situation in the Santa Clara valley of California with man as his welcome master - the Lovemaster (London could never have known how ridiculous that name would sound to today's reader - you almost expect some funky music to start after you read it the first time - the luuuvmaster). Both stories completely justify every step in the life of a dog, from loving loyalty to savage brutality.

The beauty of this reversal is only complete after reading both books - which for all intents and purposes seem to me - a first time London reader - as perfect companion novels. Both have periods of intense suffering due to poor treatment; interaction with and learning to understand humans; poignant descriptions of the reality of the call to live in complete wild freedom; and an emotional climax that involves true xenophilic love between man and beast. This last bit is best portrayed in The Call of the Wild between Buck and Thornton, a member of a small group of back-country wildmen that knows enough to respect a remarkable animal when he sees him. Those passages are so moving and well-written, they are the only bit of prose or poetry that has ever made me consider actually getting a dog. Tears are welling up for you already, I'm sure.

Because each process of role reversal in this pair of books is so carefully crafted to convince the reader that the result is within the realm of natural balance, London is telling us that mortality is a state in which conflicting forces must and can be adhered to. Whether it be the freedom of the call, or the love of the domestic relationship, either can bring a state of peace. As someone that finds it easy to be convinced that either one of these ideals is superior, I find it comforting to come to this realization through London's writing - although that may just be an excuse I use to keep myself from feeling guilty about something.

The author may not have been attempting to make universal statements of the existence of man and the mortal condition. But to bring up Hemingway again, that great author said something regarding symbolism in writing that I might apply to London's writing here "No good book has ever been written that has in it symbols arrived at beforehand and stuck in. ... But if I made them good and true enough they would mean many things." So it is with these two great dogs. London, a man with an adventurous life of his own that took place in some of the same settings these books take us, used what he knew to tell true stories about life. Anything more we read into it may be just a way for English majors to get top grades or make tenure.

However, if we do question his actual intent towards application in our lives, we only need to review one of the many passages that point directly back to ourselves. The following is a great one of these:

"There is an ecstasy that marks the summit of life, and beyond which life cannot rise. And such is the paradox of living, this ecstasy comes when one is most alive, and it comes as a complete forgetfulness that one is alive. This ecstasy, this forgetfulness of living, comes to the artist, caught up and out of himself in a sheet of flame; it comes to the soldier, war-mad in a stricken field and refusing quarter; and it came to Buck, leading the pack, sounding the old wolf-cry, straining after the food that was alive and that fled swiftly before him through the moonlight." -The Call of the WildOnce we forget we're the bat - then we can know what it is like. But then it is forgotten the moment we try to think about it and pin our finger on it. My final takeaway? I'm only really alive when I'm eating - so pass the meat.

Wednesday, June 11, 2014

Wayne's World

|

| Poster credited to worth1000.com |

The main reason why I wanted to record my thoughts on it is because of the way it dealt with the story. Normally a Hollywood comedy is so burdened by over-emphasized plot points. It becomes heavy and you just sit there counting the seconds waiting for the inevitable to happen. For that reason I find that the best pure-comedies forego the story line and just let you lay out and soak in the atmosphere and personality of the movie. What makes a good comedy is that it is full of characters that you want to spend time with in a world you want to spend time in.

With Wayne's World I was a little worried at the start as Wayne & Garth (played by Mike Myers and Dana Carvey) were getting set up to fail as they enter what is obviously a raw deal in going corporate with their public-access TV show - the main struggle of the movie - but it never spent enough time on that to drag the movie down. It thankfully glossed over all the main plot setup, coasted through the second-act escalation, and jetted right on to a joyful finale. This left more time for all the real fun like constantly breaking the fourth wall ("Hey, only Garth and I can talk to the camera!"), making fun of contemporary Hollywood (writing out "Gratuitous Sex Scene" instead of showing it), and plenty of pointlessly fun exclamations (Party on! Excellent! Schwing!). I was in a constant state of feeling pleasantly surprised as I enjoyed the little quirks and random jokes that often don't get into movies today because they are trying to follow a formula (a formula established in part by the success of the 90's SNL generation movies like this one).

While it's definitely teenage and immature, it is relatively low on the low-brow humor that seems necessary in the current comedic landscape. Some of the Judd Apatow films are thoughtfully funny, but that's in spite of the intense language and bathroom humor rather than because of it (I'm sure there are plenty who disagree - but good comedy and drama shouldn't use the crutch of ridiculously obscene language). I mean don't get me wrong, every part of the human anatomy gets its fair shake (har har). But While Wayne's World certainly wouldn't be labeled as clean, it doesn't rely solely on dirty jokes (it's PG-13 - check out a Parent's Guide for more info).

Instead, what may turn some of the younger viewers away, if seeing this for the first time, is that many of its references are a generation or two old. The Laverne & Shirley sequence or the commercial spoofs just don't make sense if you haven't seen the source material - although with those carefree, goofy smiles on Wayne's and Garth's faces, you'll laugh anyway. But I think the fact that Wayne's World helped establish this type of comedy might just cross generational boundaries.

The one thing I would've wished for more of was the actual public access TV show. I know all the old SNL skits are online whenever you like, and the pull for many of these transfers to the big screen is the ability to find who these people are, but the real charm of this movie is just watching Wayne and Garth be themselves, little to no plot line required. Rather than seeing what happens to them, Wayne's World is just an excuse to hang out with them a little longer.

Friday, February 21, 2014

Book: American Gods (Tenth Anniversary Edition) - Neil Gaiman

American Gods is like a more adult-oriented version of Percy Jackson: a human gets pulled into the comings and goings of the world of the Gods in America. The main mechanism behind how the Gods got here is that they were all brought here by people emigrating from different parts of the old world, Africa, and even the land-bridge from Asia. The Gods, the versions of them that make it to and then stay in America, and how they are supported by a dwindling mass of belief in modern times, is what the book slowly shows you throughout its length.

The frequent interludes telling the stories of the immigrants are often the best part of the book, which is written in a deliberate yet intriguing style. I listened to the expanded 10th Anniversary version of the book, which included a full cast. The author himself, Mr. Neil Gaiman, speaks the introduction, the afterword, and many of the immigrant stories. He is the best audiobook reader I've encountered (go listen to his "The Graveyard Book", even if you've already read it). Of course, his British accent is great (I wish I knew how to differentiate between types of British accents - anyone know of a guide somehere??) and he's just so calm and purposeful as he reads.

This book is all about Gaiman's interpretation of America as a conglomeration of belief. The best representation of this comes in a speech by one of the book's best character's, Samantha Black Crow. Knows by fans of the book as the "I believe" speech, it reflects a culture that can paradoxically believe in many hypocritical maxims with all sincerity. Read that speech here.

I haven't even mentioned the main character yet. His name is Shadow and he is an along-for-the-ride kind of guy, slowly learning where his place is and what his existence is worth and what it means. Perhaps he could be a representation of your average American? It depends on what you believe.

Warning: Strong language throughout. Also a few graphic sex scenes - easy to skip over without losing much.

The frequent interludes telling the stories of the immigrants are often the best part of the book, which is written in a deliberate yet intriguing style. I listened to the expanded 10th Anniversary version of the book, which included a full cast. The author himself, Mr. Neil Gaiman, speaks the introduction, the afterword, and many of the immigrant stories. He is the best audiobook reader I've encountered (go listen to his "The Graveyard Book", even if you've already read it). Of course, his British accent is great (I wish I knew how to differentiate between types of British accents - anyone know of a guide somehere??) and he's just so calm and purposeful as he reads.

This book is all about Gaiman's interpretation of America as a conglomeration of belief. The best representation of this comes in a speech by one of the book's best character's, Samantha Black Crow. Knows by fans of the book as the "I believe" speech, it reflects a culture that can paradoxically believe in many hypocritical maxims with all sincerity. Read that speech here.

I haven't even mentioned the main character yet. His name is Shadow and he is an along-for-the-ride kind of guy, slowly learning where his place is and what his existence is worth and what it means. Perhaps he could be a representation of your average American? It depends on what you believe.

Warning: Strong language throughout. Also a few graphic sex scenes - easy to skip over without losing much.

Friday, January 31, 2014

Books I read in 2013

|

| Image courtesy of Nifty Swank |

- To Have and Have Not - Ernest Hemingway

- I love Hemingway. So much. His writing is just soothing and melancholy and gently optimistic, if it can be all those things at once. This one is structurally unique for Hemingway and for novels in general, as it makes a dramatic switch in perspective in a later section of the book. Essentially it might be a treatise on the fact that how much you do or do not have to struggle for your daily subsistence does not necessarily directly affect your happiness in life. I then watched the movie, with a script written by William Faulkner. Those who have read it might ask, "How can you make a great Hollywood film out of such a book?" Faulkner's answer was the same of Hollywood today: take the main setting and characters and completely rewrite the story, then add big Hollywood actors (Humphrey Bogart & Lauren Bacall). It was great.

- Casino Royale - Ian Fleming

- This was such a fun read. My first James Bond thriller. Fleming has a great command of language that, although not as subtle and transcendent as someone like Hemingway, mirrors that great writer in how he interprets and portrays a strong-willed, passionate man with a quiet heart and a dry sense of humor. Don't get me wrong - Fleming is not making any really serious statements on the poignancy of the transient nature of life. He does show parallels bewteen gambling, love, and espionage that teach Bond a lesson or two. But it's a thriller through and through. It's fundamental, it's elegant, and it drives along by its style and not over-the-top melodrama. I loved reading it. See my full review here.

- Trails to Testimony: Bringing Young Men to Christ Through Scouting - Bradley D. Harris

- This is pretty much a must for any LDS Young Men or Boy Scout leader. Other Scout leaders, especially religious-focused, may get some good things out of it as well. I was Assistant Scoutmaster and then Varsity Scout leader. It didn't last long as I had moved, but this book helps ease you mind a bit on the many, many tasks available in scouting, allowing a leader to focus on what they see as the most essential parts of the program.

- The Count of Monte Cristo - Alexandre Dumas

- I just realized I never wrote my thoughts down on this. This was 6 months of reading. I was reading slowly but consistently - its not that the book was that hard to read - although it was large, as I read it unabridged. It was epic. It was entertaining and with lots of great lessons. I loved the interplay between the many different characters. Ultimately, though, I felt like it was kind of hypocritical. This guys goes through this entire life seemingly focused on revenge and enacting all these huge changes in others' lives, and then at the end we're supposed to believe he just changes and its all ok? I think I may have missed something here. I should review my notes. Thoughts?

- Cat's Cradle - Kurt Vonnegut

- My first Kurt Vonnegut book was a great read. It was like Paulo Coelho's "The Alchemist" in its structure of blissful coincidence, but from a cynical point of view. I love his mini chapters, each of which is a witty little whimsical thought on its own and directs the timing and rhythm for both the story-telling and the humor. It was fun and thought-provoking.

- The Fault In Our Stars - John Green

- I had really no expectations going into this book - I didn't know it was a teen book until I downloaded it (on Audible). I had noticed recommendations from a diverse range of people and the title was intriguing (I had no idea of the original reference). I'd been reading some heavier, dense, and less accessible books at the time so this was a refreshing change of pace. I was drawn in to the characters quickly and really enjoyed all the kids' distinct personalities. The love story between the two main characters is really well done in that it mostly develops slowly and deeply and is just a lot of fun to experience. And I love the quick-witted dialogue - although I don't know enough teenagers to know if there really are kids that are this brilliant and well balanced. Because, despite the situation they're in, they are pretty well balanced people - despite constant thinking of death, suffering, and pain. Of course, maybe that's the lesson. The interaction between Hazel and Gus is really the best part of the book. Check out the trailer for the movie coming out this summer.

- Ask Without Fear: A Simple Guide to Connecting Donors with What Matters to Them Most - Marc A. Pitman

- I'm a fundraiser by profession, although still early in my career. This was a nice little book read purely for professional development.

- Moving in His Majesty and Power - Neal A. Maxwell

- Neal A. Maxwell was an LDS apostle, a member of one of the senior leadership councils of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. I love his style of writing and speaking. It's characterized by simple, but profound lessons garnered from casual stories from throughout his life and favorite readings.

- I Am Legend - Richard Matheson

- Read this in a volume that is a collection of many works by Matheson, and don't look at page numbers. That way you'll be more surprised at when the book ends. While I don't think it's that noteworthy, I understand its historical and generic significance, and I love works that embody their title with a singular focus.

- How Music Works - David Byrne

- A joyous exploration of just about every philosophic aspect of music. It has just about something for everybody. My full review here.

That's it. Have you read any of these? Let me know what you thought - I love to discuss it.

Sunday, January 19, 2014

Film: The History of Future Folk

The History of Future Folk is truly a hidden gem. All you really should have to know before watching it is that it labels itself as "probably the only alien-folk-duo sci-fi-action-romance-comedy movie ever made," which just about makes it the best of its kind. That speaks volumes as to the fun these filmmakers have in store for you when you watch this movie. It's a raucously delightful indie comedy that keeps you smiling the whole time through.

The film follows General Trius, a legendary military leader from the distant planet Hondo, marooned on Earth for years after being assigned a mission to save his people from an impending comet, and with killer chops on the banjo. He goes by Bill. His mission was to find a planet to take for the people of Hondo, but he discovered something commonplace here on Earth that he had never before experienced: music. He grows to love the human race, which now includes a wife and daughter (the first half-human/half-Hondonian in the universe, I suspect).

Kevin, another Hondonian, is sent to finish General Trius' mission but ends up joining with him and forming a loveably goofy and truly rocking folk-duo. Beautiful insanity ensues as they attempt to escape the law, fight off assassins, and win the heart of the women of their dreams, all while attempting to stop the comet on its way to kill Hondo and save the planet earth from a terrible fate.

This flick's short 85-minute running time is padded with glorious, full-on musical numbers as the duo of Future Folk just can't keep from expressing how much they love music. They sing their hearts out in fantastic form about the perils of living far from Hondo and once they start you'll be begging for more (I especially loved the song "Space Worms"). This was just pure delight from beginning to end. Please go find and watch this movie. And in case you're wondering, this would qualify for an easy PG-rating (nothing more than a few shots of lasers).

Available in Video On Demand everywhere including Amazon & iTunes. Currently streaming for Netflix subscribers.

The film follows General Trius, a legendary military leader from the distant planet Hondo, marooned on Earth for years after being assigned a mission to save his people from an impending comet, and with killer chops on the banjo. He goes by Bill. His mission was to find a planet to take for the people of Hondo, but he discovered something commonplace here on Earth that he had never before experienced: music. He grows to love the human race, which now includes a wife and daughter (the first half-human/half-Hondonian in the universe, I suspect).

Kevin, another Hondonian, is sent to finish General Trius' mission but ends up joining with him and forming a loveably goofy and truly rocking folk-duo. Beautiful insanity ensues as they attempt to escape the law, fight off assassins, and win the heart of the women of their dreams, all while attempting to stop the comet on its way to kill Hondo and save the planet earth from a terrible fate.

This flick's short 85-minute running time is padded with glorious, full-on musical numbers as the duo of Future Folk just can't keep from expressing how much they love music. They sing their hearts out in fantastic form about the perils of living far from Hondo and once they start you'll be begging for more (I especially loved the song "Space Worms"). This was just pure delight from beginning to end. Please go find and watch this movie. And in case you're wondering, this would qualify for an easy PG-rating (nothing more than a few shots of lasers).

Available in Video On Demand everywhere including Amazon & iTunes. Currently streaming for Netflix subscribers.

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

Book: Slaughterhouse Five - Kurt Vonnegut

Reading this Kurt Vonnegut book is sort of like when I listened to the entire Beatles White Album for the first time. I thought, "Wow - The Beatles are amazing! This would be wildly innovative and ground breaking music TODAY but it came out 40 YEARS AGO!" It made all other music since seem not so innovative. It was the same way watching Fellinni's oddly autobiographical film about writer's-block, 8 1/2, made me think about the Charlie Kaufman written, Spike Jonze directed film Adaptation. It didn't seems quite so unique afterwards. Except for with Vonnegut I can't quite figure out what the comparison is, besides all modern writing since.

The closest thing I can get at is, in fact, a Kaufman written movie, like Being John Malkevich, the aforementioned Adaptation, or Synechdoche, NY. He uses a meandering plotline - jumping from one point in time to another along the timeline of the character (although this is explained by constant time travel) - to discuss heavy-hitting themes with a whimsical, informal style. He's basically saying, "It's so disgusting and wrong and inexplicable that its funny." The main character Billy Pilgrim's attitude is representative of the philosophy of the whole book, which is a passive acceptance of fate, expressed often after a death is described with the phrase, "so it goes."

The book describes the life of Billy Pilgrim through nonlinear time travel from one point of his life to another. This can happen at any time (and actually includes being abducted by aliens and taken to their home planet, Tralfamadore). The thing about Billy is that nothing really surprises him because he's already travelled all over his life and knows what is coming - and he just seems to accept it. The focus event of the book and of Billy Pilgrim's life is one that Vonnegut actually experienced himself: the fire bombing at Dresden, Germany, during World War II. Tens of thousands of German civilians were killed when the town was obliterated by Allied forces right near the end of the war. Vonnegut compares it to Hiroshima, and hints it might have even been worse than that in some ways. He writes himself into the book as the narrator, although his role and that of his friend O'hare, are mostly fictionalized.

But it really is so fun to read. While Dresden is central to the book, it covers the extent of Billy's whole life as he goes to optometry school, marries the school owner's daughterValencia, is abducted by the Tralfamadorians, wanders and is transported as a POW in Germany, among other things. One quick episode describes a morphine-induced dream Billy has after being injured in the war. He imagines himself in a garden with giraffes: "Billy was a giraffe, too. he ate a pear. It was a hard one. It fought back against his grinding teeth. It snapped in juicy protest." Or the one that goes, "Billy heard Eliot Rosewater come in and lie down. Rosewater's bedsprings talked a lot about that." Or the way he describes warfare as "the incredible artificial weather that Earthlings sometimes create for other Earthlings when they don't want those other Earthlings to inhabit Earth anymore." I find these little passages delightful.

And there is so much more than what I've touched on. Billy Pilgrim is such a pleasant character. As the narrator says, "Everything was pretty much all right with Billy." He sort of lets life flow over him. He finds his own existence an inconvenience, although he's not depressed. He doesn't like being around his mother for knowing what she had to go through to bring him to this life. The book is often on banned book lists for some profanity and others interpreted it as anti-Christian or immoral or fatalist. I'm not sure about any of that. I might not agree with Vonnegut on everything, but Billy says something near the end of the book that I like. He says, "Everything is all right, and everybody has to do exactly what he does." Does that mean Vonnegut is saying the terrible tragedy of Dresden is ok? (although he does give the US Army its due explanation as to why it was strategically sound). I think he's talking about how relieving it can be to accept the world around you, or rather, accept things as they happen. You should go and enjoy this book before you die. Even though many people probably don't read it before they die. So it goes.

The closest thing I can get at is, in fact, a Kaufman written movie, like Being John Malkevich, the aforementioned Adaptation, or Synechdoche, NY. He uses a meandering plotline - jumping from one point in time to another along the timeline of the character (although this is explained by constant time travel) - to discuss heavy-hitting themes with a whimsical, informal style. He's basically saying, "It's so disgusting and wrong and inexplicable that its funny." The main character Billy Pilgrim's attitude is representative of the philosophy of the whole book, which is a passive acceptance of fate, expressed often after a death is described with the phrase, "so it goes."

The book describes the life of Billy Pilgrim through nonlinear time travel from one point of his life to another. This can happen at any time (and actually includes being abducted by aliens and taken to their home planet, Tralfamadore). The thing about Billy is that nothing really surprises him because he's already travelled all over his life and knows what is coming - and he just seems to accept it. The focus event of the book and of Billy Pilgrim's life is one that Vonnegut actually experienced himself: the fire bombing at Dresden, Germany, during World War II. Tens of thousands of German civilians were killed when the town was obliterated by Allied forces right near the end of the war. Vonnegut compares it to Hiroshima, and hints it might have even been worse than that in some ways. He writes himself into the book as the narrator, although his role and that of his friend O'hare, are mostly fictionalized.

But it really is so fun to read. While Dresden is central to the book, it covers the extent of Billy's whole life as he goes to optometry school, marries the school owner's daughterValencia, is abducted by the Tralfamadorians, wanders and is transported as a POW in Germany, among other things. One quick episode describes a morphine-induced dream Billy has after being injured in the war. He imagines himself in a garden with giraffes: "Billy was a giraffe, too. he ate a pear. It was a hard one. It fought back against his grinding teeth. It snapped in juicy protest." Or the one that goes, "Billy heard Eliot Rosewater come in and lie down. Rosewater's bedsprings talked a lot about that." Or the way he describes warfare as "the incredible artificial weather that Earthlings sometimes create for other Earthlings when they don't want those other Earthlings to inhabit Earth anymore." I find these little passages delightful.

And there is so much more than what I've touched on. Billy Pilgrim is such a pleasant character. As the narrator says, "Everything was pretty much all right with Billy." He sort of lets life flow over him. He finds his own existence an inconvenience, although he's not depressed. He doesn't like being around his mother for knowing what she had to go through to bring him to this life. The book is often on banned book lists for some profanity and others interpreted it as anti-Christian or immoral or fatalist. I'm not sure about any of that. I might not agree with Vonnegut on everything, but Billy says something near the end of the book that I like. He says, "Everything is all right, and everybody has to do exactly what he does." Does that mean Vonnegut is saying the terrible tragedy of Dresden is ok? (although he does give the US Army its due explanation as to why it was strategically sound). I think he's talking about how relieving it can be to accept the world around you, or rather, accept things as they happen. You should go and enjoy this book before you die. Even though many people probably don't read it before they die. So it goes.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)