|

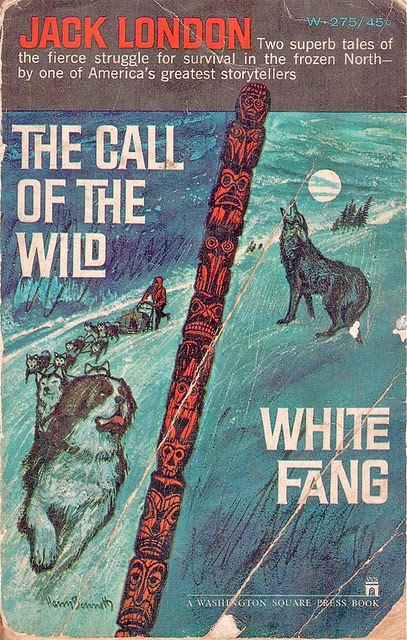

| Photo credit: m.gross196 on Flickr |

-White Fang

Thomas Nagel, an American philosopher I know very little about, wrote an essay called "What its like to be a bat" in 1974. The main point is that one can never truly know what it is like to be someone or something else. Should some power be able to transport the essence of yourself into the body of a bat, perhaps even with some of the instincts of a bat, so that you could then return and report back on the experience, you'll never have actually had the experience of being a bat. Because, by definition, being a bat is not knowing and understanding what it is to be anything else. You would only have accomplished knowing what it is like to be you in the body of a bat. And so truly experiencing what life is like in another's skin is impossible. Even so, Jack London does a helluva job describing the life of a dog in White Fang and The Call of the Wild

I'm really beginning to love Jack London. After first reading The Call of the Wild and now White Fang I am really drawn into his writing. Like Hemingway, London has a relatively bleak style, but the similarity is due more to the shared subject matter than the lack of narrative more characteristic of the former. Both writers spend a lot of time describing very basic, physical processes that suggest a natural state of being. In both of these books by London, the primary point of view is that of a wolf/dog or dog/wolf, respectively White Fang and Buck, and so while human events, actions, and words are described, the only understanding that is spelled out is that which the dog possesses. We must infer anything else that is happening - some is obvious and some unimportant and unmentioned.

They are essentially the same story told in reverse. Which is forward and which is reverse depends either on which you read first or which you prefer. One follows a dog with a bit of wolf in him and his journey from the cushy Santa Clara valley to the hard life as a sled dog in the Alaska wilderness to, finally, complete freedom as a wholly wild animal. The other follows a wolf with a bit of dog in him in the Alaska wild that learns to trust man, fear man, work for man, and eventually winds up in a cushy situation in the Santa Clara valley of California with man as his welcome master - the Lovemaster (London could never have known how ridiculous that name would sound to today's reader - you almost expect some funky music to start after you read it the first time - the luuuvmaster). Both stories completely justify every step in the life of a dog, from loving loyalty to savage brutality.

The beauty of this reversal is only complete after reading both books - which for all intents and purposes seem to me - a first time London reader - as perfect companion novels. Both have periods of intense suffering due to poor treatment; interaction with and learning to understand humans; poignant descriptions of the reality of the call to live in complete wild freedom; and an emotional climax that involves true xenophilic love between man and beast. This last bit is best portrayed in The Call of the Wild between Buck and Thornton, a member of a small group of back-country wildmen that knows enough to respect a remarkable animal when he sees him. Those passages are so moving and well-written, they are the only bit of prose or poetry that has ever made me consider actually getting a dog. Tears are welling up for you already, I'm sure.

Because each process of role reversal in this pair of books is so carefully crafted to convince the reader that the result is within the realm of natural balance, London is telling us that mortality is a state in which conflicting forces must and can be adhered to. Whether it be the freedom of the call, or the love of the domestic relationship, either can bring a state of peace. As someone that finds it easy to be convinced that either one of these ideals is superior, I find it comforting to come to this realization through London's writing - although that may just be an excuse I use to keep myself from feeling guilty about something.

The author may not have been attempting to make universal statements of the existence of man and the mortal condition. But to bring up Hemingway again, that great author said something regarding symbolism in writing that I might apply to London's writing here "No good book has ever been written that has in it symbols arrived at beforehand and stuck in. ... But if I made them good and true enough they would mean many things." So it is with these two great dogs. London, a man with an adventurous life of his own that took place in some of the same settings these books take us, used what he knew to tell true stories about life. Anything more we read into it may be just a way for English majors to get top grades or make tenure.

However, if we do question his actual intent towards application in our lives, we only need to review one of the many passages that point directly back to ourselves. The following is a great one of these:

"There is an ecstasy that marks the summit of life, and beyond which life cannot rise. And such is the paradox of living, this ecstasy comes when one is most alive, and it comes as a complete forgetfulness that one is alive. This ecstasy, this forgetfulness of living, comes to the artist, caught up and out of himself in a sheet of flame; it comes to the soldier, war-mad in a stricken field and refusing quarter; and it came to Buck, leading the pack, sounding the old wolf-cry, straining after the food that was alive and that fled swiftly before him through the moonlight." -The Call of the WildOnce we forget we're the bat - then we can know what it is like. But then it is forgotten the moment we try to think about it and pin our finger on it. My final takeaway? I'm only really alive when I'm eating - so pass the meat.

That copy was mandatory reading for my Uncle back in the '50s/early '60s. Kids don't read classics like this anymore...

ReplyDelete