|

| How old do they look to you? |

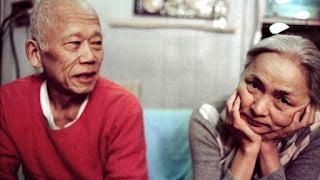

As I mentioned in my last post I had an opportunity to attend the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and see Cutie and the Boxer, a documentary film by Zachary Heinzerling about Ushio and Noriko Shinohara, an aging Japanese married couple - both artists - living in New York City. As I've reflected on the film one of the most prominent thoughts that surfaces is age.

Age is perhaps our most defining physical characteristic. Maybe even more than race. And just like race and ethnicity, the physical cues that point to age can be misleading. It's easy to judge someone based on how old we think they are. We look at someone and we can make a guess. But while age is a reflection of the experiences gained through years lived and seen outwardly through the physical body, it's just a number. The identity of the person inside the body is not bound to any notion others have about how old they are. At any age we can be misjudged because of how old we look. As we get older some people define themselves less by their age and focus more on the way they feel. Maybe that's why I can't remember my age that well. That or I'm just getting older. In Cutie and the Boxer we see first an older couple, and then throughout the film we see more of who they really are and how they see themselves.

Zachary Heinzerling's documentary Cutie and the Boxer is not a film primarily about age, although it invokes thoughts about aging. It's a film about the relationship between a husband and a wife and the sacrifices it takes to dedicate your life to someone else. Back when they first met, Ushio was already a prominent avant garde artist, having made an impact in Japan and rubbing shoulders with people like Andy Warhol in New York. He was most famous for his boxing paintings. To create these pieces of art Ushio dresses himself up very much like a boxer, including strapping on boxing gloves with sponges dipped in paint. He then energetically punches a large canvas as he moves from right to left. The experience of creating these paintings, which takes only a couple of minutes, epitomizes who Ushio is and how he sees himself as an artist. He appreciates characteristics like power, energy, spontaneity, and movement. Also famous for his motorcycle and dinosaur sculptures, he likes to name his exhibits with words like "Vroom!!" and "Roaarrr!"

|

| Ushio and Noriko Shinohara |

According to her own story, Noriko was a young and eager artist fresh off the boat. She met Ushio, over 20 years her senior, and quickly entwined her life with his, giving up her own aspirations as an artist in the process. Jump forward after a child and 39 years of marriage and we them first as any other couple, with their quirks and recurring arguments. It seems the family focus has been on Ushio's career. We quickly realize that Noriko set a precedence very early on in their relationship by making significant sacrifices in her lifestyle to accomodate Ushio and his needs. Now, after four decades together, she's undergoing a retrospective of her life and breaking out as the artist she always meant to be. Ushio's career seems to be gaining new momentum as well.

The film follows from there, laying out small but defining interactions between Ushio and Noriko over a two-year period. Beautifully filmed and beautifully portrayed, it splices in principal photography, archive footage covering multiple periods of their life, and the fantastical world of each of their art - especially the animation of Cutie's world. The animation is based on Noriko's comic about Cutie and the Bullie, her caricatured interpretation of herself and Ushio. Much of their history is told through a creative process bringing her drawings to life. These vignettes fill out how these two amazing people arrived to become who they are now, but all from her perspective. Although the film is about both of them, she outshines as the main character.

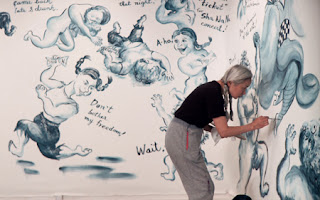

|

| Creating Cutie |

During the Q&A the director was asked why he decided to call the film Cutie and the Boxer when Noriko's comic named them Cutie and the Bullie. He answered that it just sounded better to him. I think the better answer - which he probably could've answered - is that it reflects the identity each of the characters would give themselves, even though neither is completely accurate. It's how they see their idealized selves. Noriko envisions herself as Cutie, the independent female artist able to overcome and tame her love-needy but headstrong husband. Ushio sees himself as the prize fighter and artistic genius of the family, his boxing paintings as a symbol of his power and art and therefore his dominance in their relationship. The reality of how each of these identities has manifested over the years is the result we see on the screen. Ushio surges ahead as the blind ambition in the family while Noriko quietly tweaks their trajectory, displaying the self awareness Ushio is incapable of conjuring.

|

| Roarrr!! |

It's true that at first glance the film can seem to portray Ushio as uncaring, prideful, and jealous. It's an example of one of those relationships where the woman, due to the man's negligence and denial, has to take over the practical functioning of the family. But Heinzerling also hinted at something that the movie subtly tells you as you watch: that Ushio is a good and dedicated man and that he and Noriko have come to an unspoken arrangement. Ushio has a vibrant and open personality and is honest, but his love is need-based. And, although she has struggled with it for their 40+ years together, Noriko is ok with that. She might even be willing to do it all again.

As a final note, the original score is a poignant, piano-based accompaniment that feels greater than itself. I couldn't help but compare it to music of Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli films (especially Spirited Away). Composed by Yasuaki Shimizu, it has a quiet introspective feel. (Check out Yasuaki's own saxophone interpretation of Bach's Cello Suite no. 1). Like in all the best movies, the score helps to drive home the emotional impact from the story on the screen. And it might even make you forget your age.